The Heart of Software Engineering Still Beats

A few weeks ago, I had a conversation that’s stayed with me. A colleague from another department said: “I’ve always been able to read and understand code, even debug it, but I could never write it.”

Something about this revelation stayed with me. Most people I’ve met outside the software engineering world tend to describe code as unintelligible - like hieroglyphics. I guess that’s why I’ve always assumed: if someone couldn’t write code, they probably couldn’t read it either.

But this person isn’t a software engineer. They don’t work in a role where coding is expected. And yet, they can read it. Follow its logic. Understand enough to debug it.

That was new to me. I’ve worked with plenty of people who can’t code - that’s normal. But someone who can read code fluently, yet feels unable to write it, struck me as an unusual inversion of what I’d always assumed.

Modelling, Not Just Typing

Writing code isn’t just knowing syntax. It’s not just about conditionals or classes or regexes. At its heart, writing code is modelling - the ability to form a structured mental model of a process, a system, or an idea, and then encode it in a way that a machine can understand.

What you’re creating is a representation: a digital reflection of something real, or imagined. Sometimes that model lives in your head. Sometimes it spills out across a whiteboard or a sheet of paper. But it’s always there - an abstraction you’re building, refining, naming. You’re spotting patterns, finding generalisations, shaping structure from chaos. And then translating all of it into syntactically correct code.

This is what’s always drawn me to programming. The act of shaping a mental image, refining it through thought, and watching it come to life. Even today, after decades in this industry, there’s still something magical about it.

As Fred Brooks, author of the very famous book The Mythical Man-Month, put it:

The programmer, like the poet, works only slightly removed from pure thought‑stuff. He builds his castles in the air, from air, creating by exertion of the imagination...

— Frederick P. Brooks, The Mythical Man-Month, Chapter 1, Addison-Wesley, 1975

That image - that castle in the air - is what draws many of us to code. It’s abstract, fragile, and yet, when the build succeeds, it becomes something real. A living, running representation of our ideas.

And we don’t get there by accident. The transition from mental model to working system happens through design - a process of making trade-offs, choosing abstractions, and shaping the code in a way that reflects not just what works, but what makes sense.

Design Isn’t a Phase

In some organisations, design is treated as a one-off activity. It happens at the beginning of a project, often in a different room, done by someone else with a different title. Sometimes it’s even handed down like a blueprint to be implemented.

But anyone who’s spent time building software knows: design is everywhere. It’s in how you break down a problem. In the abstractions you choose. In the edge cases you decide to handle - or not. Design happens during implementation, during testing, during bug fixing, and even while reading logs to understand why something failed in production.

John Ousterhout said it plainly in his recent interview with Gergely Orosz:

My personal belief is that design permeates the entire development process. You do it upfront, you do it while you're coding, you do it while you're testing, you do it while you're fixing bugs; you should constantly be thinking about design.

— John Ousterhout, interview with Gergely Orosz

Design isn’t a step we move past - it’s how we evolve our representations. It’s how we learn what we missed, or overcomplicated, or misunderstood. And it’s deeply satisfying. There’s a quiet joy in realising you’ve found a better way to shape something. That your system is more robust, more elegant, more humane because of it. Sometimes that shift is architectural. Sometimes it’s a single line. The devil might be in the details - but so is the beauty. And that’s where the craft lives too.

A Memory That Still Moves Me

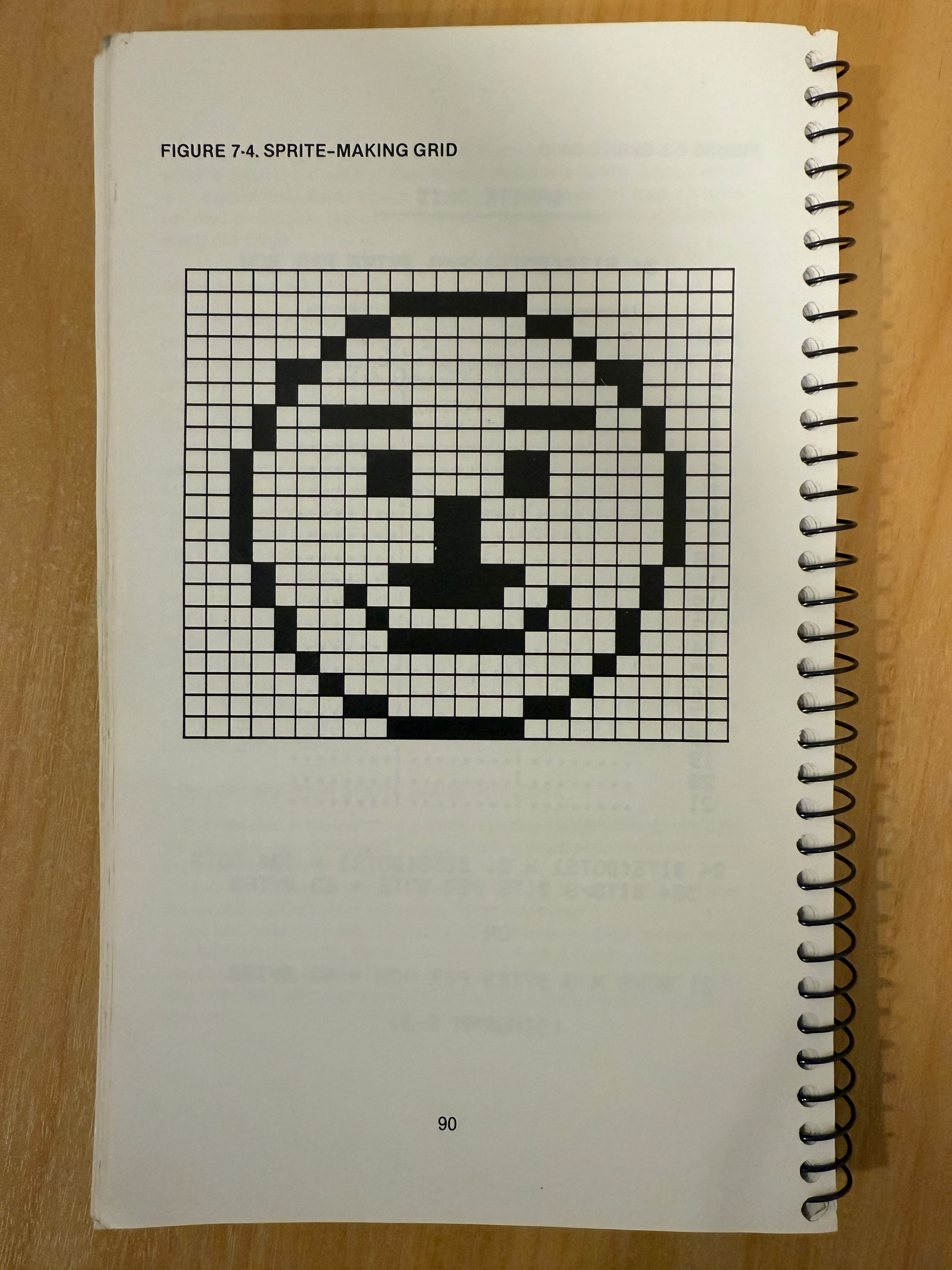

I still remember the first time I saw an idea come to life on screen. I was six years old, sitting at my Commodore 64, carefully typing out lines from a manual I barely understood.

There were no variables to name. No functions to design. I was just copying commands - faithfully, line by line. I didn’t know what a loop was, or what DATA meant. But I typed RUN, pressed RETURN, and something happened.

A face appeared.

My first creation in BASIC, from the Commodore 64 manual

Not a great one. Just a blocky pixel sprite. But it moved. It smiled at me from the screen, and I smiled back - stunned that text I’d typed had become something visual that moved.

I wasn’t designing anything of my own. I wasn’t solving a problem or building a system from scratch. But at six years old, that didn’t matter. Seeing those symbols turn into something alive on screen was enough to hook me for life.

Looking back now, I realise what captivated me wasn’t the syntax. It was the revelation of possibility - that words could become images. That logic could shape behaviour. That you could model something invisible, nothing more than pure thought, and then run it.

Even now, decades later, that moment still moves me.

What We Learned to See

Over time, the magic becomes more than just the image on the screen. You start to notice what’s behind it.

The way the code is structured. Where it flows, and where it fights itself. You begin to feel when a function is doing too much. When an abstraction leaks. When a variable name is quietly misleading.

You might hear about these principles in lectures or read them in books, but theory alone doesn’t stick. It’s when you inherit a codebase that fights you at every turn that you truly understand why these things matter. When you spend hours untangling what should have been simple. When you feel the cost of all those shortcuts taken over the years.

That’s when you develop an intuition - an internal radar for what’s brittle, what’s elegant, what’s deceptively complex.

Code starts to feel less like a puzzle to solve and more like a conversation to understand. You begin to recognise fingerprints. This bit was clearly rushed. That bit was lovingly crafted. This change came from someone who knew the system inside out. That one… maybe not.

In this evolution, the magic deepens. What started as wonder at seeing code come to life on screen becomes appreciation for how we organise thought itself. Writing code isn’t just how we instruct a machine - it’s how we give shape to our own understanding. A way to turn thought into structure. Intent into form.

The Test We All Had to Pass

For many of us, reading and writing code wasn’t just a skill, it was a test. Quite literally.

Coding interviews. Live whiteboarding. We were asked to write functions from scratch, under pressure, with someone watching. We weren’t just trying to solve problems - we were trying to show our thinking.

We prepared diligently. Memorised sorting algorithms. Practised recursion and dynamic programming. Optimised for time and space complexity. And for all their flaws, these interviews taught us something. They taught us how to trace logic out loud. How to structure an approach. How to fail gracefully, and recover.

For some, platforms like LeetCode and HackerRank evolved beyond mere preparation. They became a kind of personal challenge. A way to stay sharp. To prove to yourself that you still could. Leaderboards and contests sprang up, and with them, a sense of competition. Bragging rights. Mastery, on display.

We wore those battle scars with pride. Not because the process was fair, but because it was hard. Because it demanded something real from us: our ability to model, abstract, and express ideas clearly, under pressure.

It was stressful, yes. Sometimes unfair. But it reinforced that writing code was a kind of thinking - a visible trace of our structured understanding. And being good at it meant being able to shape those models quickly and clearly.

And now?

Well, it’s complicated. AI coding assistants can pass these tests too. They can write elegant solutions. Sometimes better than we can. They don’t get nervous. They don’t forget to handle an edge case. They just… output.

Which makes you wonder: if the thing that defined at least part of our entry into this field can now be automated, what does that mean for what comes next?

A Shift That Feels Personal

Maybe that’s why the rise of generative AI is hitting us in a different way. It’s not just about productivity gains. It’s about what’s being displaced.

A few months ago, I wrote a post called The Software Engineering Identity Crisis. It clearly struck a nerve - almost 60,000 views in just a few weeks. Dozens of engineers reached out personally to share their experiences. The message was consistent: “Yes. This is exactly what I’ve been feeling, but hadn’t put into words.”

There’s a quiet discomfort rippling through our industry. And I think this is part of it.

We’ve spent years honing a craft that’s part logic, part intuition, part art. And now we’re watching tools - not just assist us, but perform the very thing many of us took deep pride in: that mental modeling, that translation of abstract thought into executable form.

A recent New York Times article captured this tension. Titled At Amazon, Some Coders Say Their Jobs Have Begun to Resemble Warehouse Work, it describes how some engineers feel monitored, controlled, and pushed to deliver at unrelenting speed, echoing the dynamics of factory labour. The piece suggests a subtle but profound shift in the nature of engineering work: from craft to throughput. From autonomy to optimisation.

And one line hit particularly hard:

This shift from writing to reading code can make engineers feel as if they are bystanders in their own jobs.

— The New York Times, May 2025

This is what devaluation can look like. Not being replaced, but being sidelined. The moments we used to savour - the ones that brought flow, and joy, and pride - are becoming rarer. Shorter. Edged out by something faster, more efficient, and strangely hollow.

We’re adapting, yes. But part of us is grieving too.

Finding Our Place

There’s no denying it - this technology is absolutely incredible. It can write code that many people feel they never could. But along with that comes a sense that something uniquely human is being devalued - that creative spark that transforms abstract thought into working systems.

In the art community, a similar conversation is happening. Artists have started using “Created with Human Intelligence” badges on their work.

Beth Spencer - Created with Human Intelligence

Kick-started by Beth Spencer, this is a quiet rebellion against the tide of AI-generated content. Not because AI art isn’t impressive, but because there’s something worth preserving in the human creative process itself.

Don’t get me wrong - I’m not suggesting we resist progress. The world is changing, and we need to change with it. This shift is opening up new possibilities we’re only just beginning to explore. But I still carry a deep appreciation for the moments when code felt like pure magic - when shaping an idea into something runnable brought clarity, joy, and a sense of creation that was entirely our own.

The future of software engineering is being redefined before our eyes. If you, like me, have taken pleasure in the creation of code, we need to find new ways to experience that same satisfaction. These tools are improving rapidly, and businesses are eager to leverage them to their full potential.

For now, we still need to guide these assistants carefully. But that will change over time. The question becomes: how do we preserve what matters most about our craft while embracing what comes next?

From Prompts to Context

At its core, programming has always been about modelling - taking something abstract and giving it a structure that can run. Sometimes we do that by writing code. But more and more, we’re doing it by shaping the context around a tool that writes the code for us.

Prompt engineering felt like the next abstraction layer. A clever way to influence the output. And for a while, it was.

But as these tools evolve, we’re learning that the real power isn’t in the prompt. It’s in the context. The true challenge lies in encoding the messy real world into something a machine can work with - that’s far harder than simply generating code.

Is context engineering the new prompt engineering?

The systems that perform best aren’t those with the cleverest prompts - they’re the ones with the clearest scaffolding. Good documentation. Consistent naming. Representative examples. The kind of subtle cues that help an AI understand what good looks like in your specific context.

As Ibrahem Amer explains in his article on prompt engineering versus context engineering, this approach involves multiple layers: from foundational knowledge structures to data integration systems to the moment-by-moment context delivery. It’s not just about crafting clever instructions - it’s about building an entire environment in which the AI can operate effectively.

And this changes how we show our skill.

It’s not about being a prompt whisperer. It’s about structuring what the tool sees. Giving it the right framing. Guiding its attention. Helping it learn from the materials we’ve already shaped.

In other words, we’re still designing systems. Still modelling complexity. Still shaping abstractions.

The shape of our work may be changing. But the underlying skill - the ability to see clearly, structure thoughtfully, and model well - remains at the heart of it all.

The Convergence of Tool and Component

This shift in skill - from crafting code to crafting prompts, and now, to crafting context - becomes even more important when we realise that AI isn’t just helping us build software; it’s becoming part of the software itself.

AI is no longer just a tool we use to build software. It’s becoming a component inside the systems we build. But when we use AI to help us build software that contains AI… where does the boundary lie?

The distinction starts to blur. The AI becomes both the engine and the product - at least, that’s how it can feel. And while the boundary is blurry in practice, thinking of them separately can still be a helpful distinction, especially when things start to feel fluid.

This idea resonated strongly with me during Simon Warden’s talk, AI as the Engine, Not the Product, at the YOW! Tech Leaders Summit. He articulated how the most successful AI implementations aren’t those that just expose capabilities, but those that orchestrate them thoughtfully within systems.

We’re still engineers. But the materials have changed.

The skill isn’t vanishing. It’s resurfacing - at a different altitude.

The Joy, Reframed

We still model things that don’t exist yet. We still shape invisible systems out of thought and logic and names. We still give form to ideas.

That joy hasn’t gone. But its expression is shifting.

Today, AI handles more of the syntax. More of the scaffolding. But the architecture - the imagination behind it - is still ours to hold. The abstractions we shape. The intent we encode. The representations we choose.

And maybe now, with these tools beside us, we can go further. Be bolder. Imagine more ambitious castles. Explore stranger terrain. Spend less time typing - and more time thinking. Designing. Modelling.

Because the real craft of software engineering was never about just writing code. It was always about what we were encoding - and why.

That hasn’t changed.

So let’s not forget the craft. Let’s not leave it behind.

Let’s carry it forward - clearer, faster, and maybe even more joyful than before.

We’re not losing our craft. We’re being asked to deepen it. And that’s a challenge worth accepting.