A Whole New World

In the years I’ve been building software, I’ve lived through more than a few waves. My first taste of code was in the mid‑80s, typing BASIC into a Commodore 64 where you couldn’t even save your work to a hard drive. In the mid‑90s, scripting in mIRC and hand‑rolling simple HTML sites felt cutting edge. The early 2000s were all about desktop apps, then web apps that suddenly got a lot more dynamic - yet for a while, Flash was still the only way to refresh part of a page without the user hammering the browser’s refresh button. Then AJAX arrived and changed that.

After that came an explosion of tools and technologies. On the application side, we reached for caches, queues, NoSQL databases, and event streams to make distributed systems possible and keep them performing under load. On the delivery and infrastructure side, DevOps pipelines and automated static analysis tools helped us ship faster, automated testing gave us confidence in what we were releasing, and cloud and infrastructure‑as‑code let us scale in a far more programmatic way. Mobile in the 2010s brought a whole new set of tools and constraints with it - you had to really think about payloads, because pushing huge amounts of data over mobile networks just wasn’t a great idea.

These are the kinds of shifts we point to when we talk about why software engineering is a career where there’s always more to learn. New technologies arrive constantly, and if you want to build the right solutions with the tools available today, you have to keep up, experiment, and learn how to put those tools to work in meaningful ways.

What’s exciting now is that with Gen AI, we’ve added a whole new kind of component to that toolkit: the LLM. We can weave it into our systems in all sorts of ways - as a helper inside a feature, as the thing that orchestrates tools and workflows, or as the layer that sits in front of everything and talks to users. By its very nature, though, it’s non-deterministic and often unpredictable. That forces us to rethink how we design software end-to-end, from architecture and implementation through to testing, deployment and the way we run these systems in production.

From deterministic to non‑deterministic systems

In a recent conversation between Martin Fowler and Gergely Orosz, Martin puts his finger on this very point: the importance of the introduction of non-determinism into our systems. He leans on his wife’s world of structural engineering, where one must think in terms of tolerances and deliberately build extra capacity into a bridge or a building because materials like wood, concrete and steel all vary. You can never assume two pieces of timber will behave identically. Instead, you learn as much as you can about the materials and then design around that uncertainty. I think he’s right that we’ll need a similar mindset when we work with non‑deterministic AI components, understanding the “tolerances” of that uncertainty and resisting the temptation to skate too close to the edge, especially on the security side.

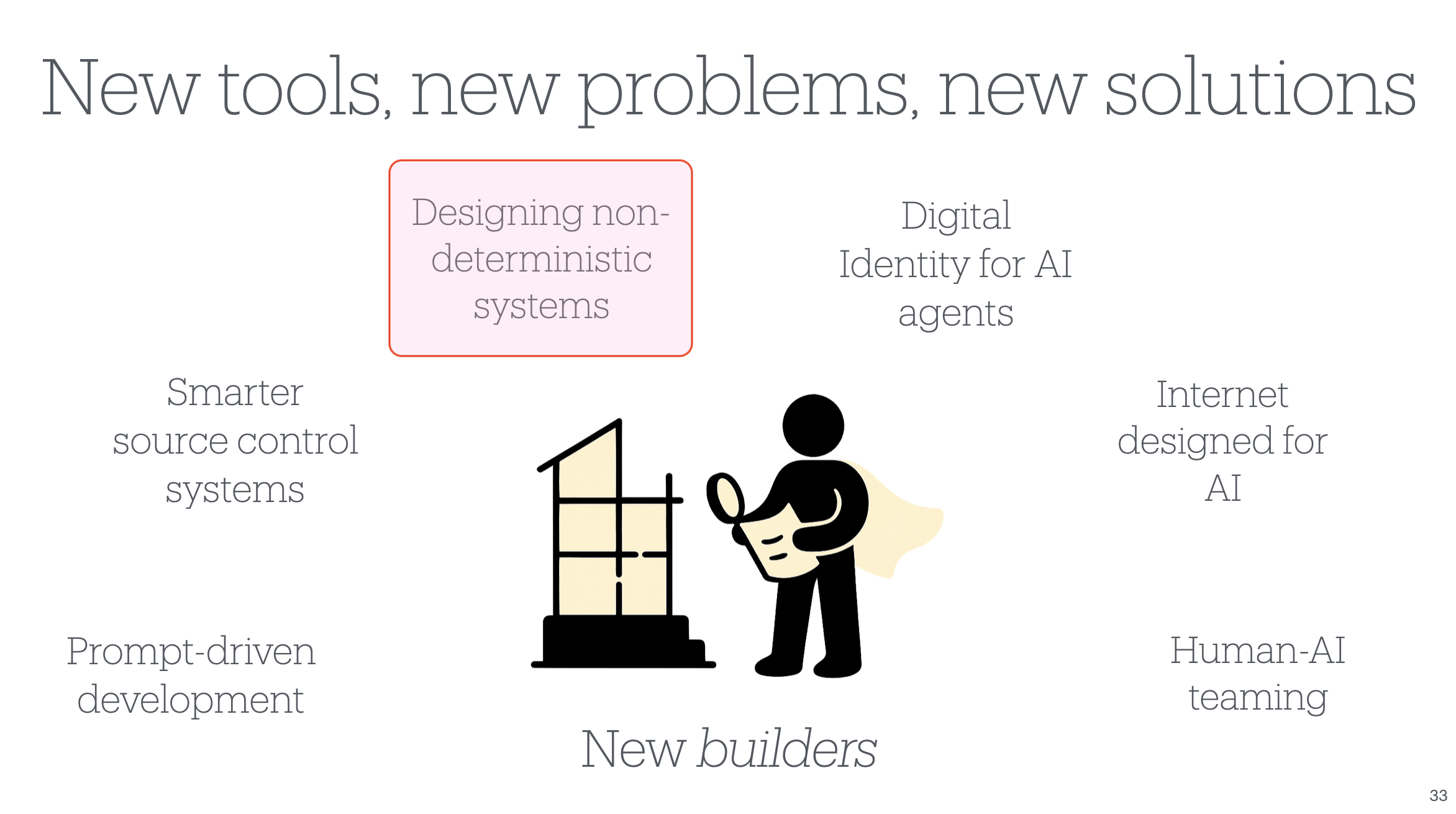

In my AI Native DevCon talk six months ago, Am I Still a Software Engineer If I Don’t Write the Code?, I shared a slide titled “New tools, new problems, new solutions” to illustrate some of the new problem spaces opening up for us as engineers. Basically, this post zooms in on just one of those boxes: designing non-deterministic systems.

From my AI Native DevCon talk Am I Still a Software Engineer If I Don’t Write the Code? This post focuses on one of these areas: designing non-deterministic systems.

The rise of the AI application layer

Up until recently, most of my research has focused on what AI is doing to software engineering as a discipline: how it changes the process of building software, what it does to our day‑to‑day experience as engineers, and how it shifts where we spend our time when we have an AI assistant sitting beside us in the IDE. But I’m just as intrigued by what it means for the software itself. The kinds of systems we can now build. The architectures we reach for. The new constraints we run into and the new classes of problems we have to solve when a non‑deterministic component sits in the middle of everything.

That curiosity has led me to focus more on the AI application layer - the part of the stack where models, tools and products actually meet real users. And there are strong signals that this focus is well‑placed. Andrew Ng, in a recent Batch editorial, pointed out that while huge amounts of money and attention are flowing into infrastructure and foundation models, the AI application layer is comparatively under‑invested. There’s a lot of value still to be created there, and that value will come from people who know how to design, build and operate these new kinds of systems.z

We’re already starting to attach more specific labels to those people - titles like AI Engineer, AI Application Developer, or AI Application Architect - folks who live closer to that layer. But I don’t think of that as a separate profession. Just as we once had to learn our way around caches, queues, mobile constraints and cloud tooling, this is simply the next set of tools and patterns we need to get fluent in. We’re still software engineers, and these are tools, patterns, and ways of thinking that we’ll be better off knowing, whether or not we ever put “AI” in our job titles.

This post is my working map of the skills and concepts I think matter for software engineers who want to build in this new LLM / agentic paradigm.

How the work shifts

Before diving into the detail, it helps to name the kinds of work that shift when you bring LLMs and agents into the mix. There is still solution design and architecture, but instead of just deciding where your service boundaries lie, you’re deciding what belongs in deterministic code vs a model, where to introduce retrieval or agents, and how to build in safety and human oversight from the start.

There is still engineering, but more and more it means stitching together models, tools, data stores, workflows and observability into something coherent and operable. A lot of the hard work now is in learning the new tooling and patterns well enough that you can keep systems explainable and debuggable, even when some core components are probabilistic.

And there is still validation, but it looks very different from traditional unit and integration testing. You need new ways to evaluate behaviour over time, catch regressions when models or prompts change, and decide what “good enough” means for systems that will never be perfectly predictable.

AI Engineering Competency Map

What follows is a set of skill areas and capabilities you can explore if you want to get serious about building systems with LLMs and agents at their core. This is simply my current view, shaped by what I’m reading, what I’m building, and what I’m seeing across the industry, not a set of hard rules or a checklist to complete. It’s deliberately broad, not exhaustive, and almost certain to evolve as the tools, patterns and best practices do.

1. Models, Providers & Core Stack

Understanding which models exist, what they can do, and the core stack used to work with them.

1.1 Model providers

Knowing the major commercial and open model providers and how to integrate their APIs.

1.2 Model capabilities & selection

Choosing appropriate models based on capability, risk and constraints.

- Reasoning depth vs latency

- Text-only vs multimodal

- Context length and token limits

- Cost profiles and rate limits

- Fine-tuned vs general-purpose models

1.3 Core implementation stack

Using programming languages and runtimes suitable for AI-enabled backends and agents.

- Python

- TypeScript / JavaScript

- Go

- C# / .NET

- Basic familiarity with async patterns and HTTP APIs

⸻

2. Knowledge Preparation & Retrieval (RAG)

Preparing data and retrieving it so agents can ground their answers in real information.

2.1 Knowledge preprocessing

Transforming messy input into clean, LLM-ready text.

- PDF to HTML or markdown

- OCR and image-to-text

- Normalising and cleaning documents

- Splitting large files into logical sections

2.2 Chunking strategies

Breaking documents into useful pieces for retrieval.

- Fixed-size vs semantic chunking

- Sliding windows and overlap

- Section- and heading-aware splits

- Trade-offs between granularity and context

2.3 Embeddings & vector search

Representing text as vectors and searching semantically.

- Embedding models and dimensions

- Similarity metrics (cosine, dot-product, etc.)

- Indexing strategies

- Handling updates and re-indexing

2.4 Hybrid retrieval & reranking

Combining different retrieval techniques to get better results.

- Keyword search (BM25 or equivalent)

- Hybrid search (keyword + vector)

- Reranking candidate documents

- Balancing recall vs precision

2.5 Knowledge graphs & structured stores

Using structured knowledge to support reasoning and answering.

- Entity and relationship modelling

- Graph databases

- Joining graph lookups with LLM answers

- When to use graphs vs plain RAG

2.6 Common vector and search backends

Using production-ready services for retrieval.

- Pinecone

- Weaviate

- Azure AI Search / Cognitive Search

- Elastic with vector capabilities

- Chroma or similar developer-oriented stores

⸻

3. Context & Conversation Management

Deciding what the model sees, how it sees it, and how to cope with context limits.

3.1 Context engineering

Designing prompts and context to give the model what it needs and nothing it does not.

- System / user / tool message structure

- Injecting retrieved knowledge and constraints

- Representing user state and persona

- Avoiding irrelevant or distracting information

3.2 Context window architecture

Managing the limited context window as a resource.

- Token budgeting across instructions, history and retrieved chunks

- Policies for what to keep vs drop

- Per-turn context templates

- Handling very long workflows or conversations

3.3 Compaction and summarisation

Compressing history while preserving what matters.

- Conversation summarisation

- State distillation into notes or facts

- Periodic “snapshot” summaries

- Trade-offs between fidelity and brevity

3.4 Structured outputs & schemas

Ensuring outputs are machine-friendly and predictable.

- JSON and typed schemas

- Function / tool call definitions

- Validation and error handling

- Strategies for recovering from malformed output

⸻

4. Agent Reasoning & Orchestration Patterns

How agents think, break down work and orchestrate multiple steps or tools.

4.1 Prompt chaining

Breaking complex tasks into explicit, ordered LLM calls.

- Multi-step workflows

- Passing intermediate outputs between steps

- Designing reusable chains

- Handling failure at intermediate steps

4.2 Routing

Selecting the right model, tool, or agent for a given request.

- Heuristic routing rules

- LLM-based router prompts

- Routing by complexity, sensitivity or domain

- Combining cost and quality constraints

4.3 Parallelisation

Running independent tasks concurrently to improve throughput.

- Fan-out calls to tools or models

- Aggregating and merging results

- Handling partial failures

- Timeouts and cancellation strategies

4.4 Planning & goal management

Creating and adjusting plans to meet explicit goals.

- Turning user goals into sub-tasks

- Ordered and dependency-aware task lists

- Replanning when state changes

- Tracking progress against a goal

4.5 Goal setting & monitoring

Defining success criteria and checking whether they are met.

- Clear definitions of “done”

- Agent-visible metrics or checkpoints

- Self-assessment cycles (“did I achieve the goal?”)

- Triggering escalation if goals cannot be met

4.6 Advanced reasoning techniques

Using structured reasoning styles to improve accuracy.

- Chain-of-Thought (step-by-step reasoning)

- Tree-of-Thought and exploring multiple paths

- ReAct (reasoning plus acting with tools)

- Self-correction and iterative refinement

⸻

5. Tools, Skills & External Systems

Connecting agents to external capabilities and designing those capabilities well.

5.1 Tool and function calling

Letting the model invoke deterministic operations.

- Tool interface design and arguments

- Idempotent and side-effecting tools

- Handling tool failures and retries

- Limiting what tools are available when

5.2 Tool ecosystems and MCP

Organising tools into discoverable, reusable ecosystems.

- Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers and tool definitions

- Describing resources and prompts

- Versioning and compatibility

- Discoverability and documentation

5.3 Enterprise and SaaS integration

Connecting agents to real systems to actually do work.

- REST and GraphQL APIs

- Databases and data warehouses

- Enterprise services (CRM, ticketing, HR, core systems, etc.)

- Handling authentication, rate limits and quotas

⸻

6. Multi-Agent Systems & Inter-Agent Communication

Using multiple specialised agents that collaborate over well-defined protocols.

6.1 Role-based multi-agent design

Assigning clear responsibilities to different agents.

- Specialist vs generalist agents

- Manager–worker patterns

- Critic/reviewer agents

- Domain vs workflow roles

6.2 Collaboration patterns

Structuring how multiple agents work together.

- Sequential hand-off

- Parallel teams aggregating results

- Debate or “argue then agree” patterns

- Escalation to higher-authority agents

6.3 Inter-agent communication standards

Using standard protocols so agents from different frameworks can talk.

- Agent cards describing capabilities

- Task and message formats

- Artifacts and streaming results

- HTTP / JSON-RPC based interaction

6.4 A2A-style discovery & interaction

Finding and calling remote agents reliably.

- Well-known URIs and registries

- Context identifiers for long-running tasks

- Polling vs streaming updates

- Security boundaries between agents

⸻

7. Memory & Learning

Giving agents continuity over time and allowing them to improve.

7.1 Short-term memory

Tracking state within a session or workflow.

- Conversation buffers

- Current plan and sub-task state

- Local scratchpads for reasoning

- Limits and reset strategies

7.2 Long-term memory

Persisting information across sessions and tasks.

- User preferences and profiles

- Project or case histories

- Vector memories and knowledge bases

- Expiry, pruning and privacy controls

7.3 Learning and adaptation

Letting systems improve from feedback and data.

- Reinforcement learning and preference learning

- Updating retrieval corpora and memories

- Policy updates from evaluation results

- Guarded finetuning where appropriate

⸻

8. Safety, Robustness & Human Partnership

Keeping systems safe, resilient and aligned with people.

8.1 Guardrails and content safety

Preventing harmful, non-compliant or out-of-scope behaviour.

- Input validation and sanitisation

- Output filtering and safety checks

- Behavioural constraints in prompts

- Dedicated safety models or agents

8.2 Exception handling & recovery

Dealing gracefully with errors and degraded conditions.

- Error detection and logging

- Retries and fallbacks

- Graceful degradation of features

- State rollback and escalation

8.3 Human-in-the-loop collaboration

Designing for human oversight and joint work.

- Human review for sensitive actions

- Escalation policies and thresholds

- Feedback loops to improve agents

- Interfaces for humans to correct or override

8.4 Security & access control

Keeping data and capabilities properly protected.

- Authentication and authorisation

- Least-privilege tool and data access

- Secrets management

- Network and tenant isolation

⸻

9. Resource & Priority Management

Using time, money and compute wisely while choosing what to do first.

9.1 Resource-aware optimisation

Balancing quality against time and cost.

- Choosing between cheap vs expensive models

- Latency-sensitive vs offline workflows

- Bandwidth and storage-aware strategies

- Fallback models and graceful degradation

9.2 Task and goal prioritisation

Deciding which task or goal the agent should work on next.

- Scoring by urgency, impact and dependencies

- Scheduling and queues

- Dynamic reprioritisation as conditions change

- Aligning agent priorities with business objectives

⸻

10. Evaluation, Monitoring & Operations

Making sure systems work, stay healthy and improve over time.

10.1 Evaluation and metrics

Measuring whether the system is actually good.

- Accuracy, relevance and helpfulness metrics

- RAG-specific metrics (faithfulness, grounding)

- Human rating workflows

- Benchmark and regression suites

10.2 Monitoring & observability

Watching live systems and catching problems early.

- Latency and error tracking

- Token and cost usage monitoring

- Concept drift and behaviour drift detection

- Logs and traces for auditability

10.3 LLMOps / AgentOps

Running AI systems as first-class production services.

- CI/CD pipelines for prompts, tools and configs

- Versioning of prompts, models and policies

- Canary and shadow deployments

- Rollbacks and kill switches

⸻

11. Frameworks, Platforms & Tooling

Using the ecosystems that make all of the above practical.

11.1 Orchestration and agent frameworks

Building complex workflows without reinventing the wheel.

- LangChain, LlamaIndex, Semantic Kernel

- CrewAI, AutoGen, Swarm-style frameworks

- Google ADK and similar agent toolkits

- Hugging Face ecosystems (model hub, Inference, Spaces)

- Local model tooling and runtimes (for example LM Studio)

- Workflow engines and state machines

11.2 Cloud AI platforms

Using managed services for models and agents.

- Azure AI Foundry

- Copilot Studio

- AWS Bedrock

- Vertex AI and similar

11.3 Evaluation & monitoring tools

Leveraging specialised tools for analysing behaviour.

- LangFuse

- Helicone

- Weights & Biases

- General observability stacks (Prometheus, Grafana, Datadog, Honeycomb, etc.)

11.4 Document and data tooling

Supporting ingestion and preprocessing at scale.

- Unstructured.io and PDF parsers

- ETL and data pipelines

- Storage backends for datasets and document collections

- Connectors into enterprise systems

Where this leaves us

This list is intentionally dense and a little overwhelming, because the space itself is. You don’t need to become an expert in every item in this list; getting comfortable with even a handful of them will open up new kinds of systems to design and new questions to wrestle with, in a space where many of the patterns and “best practices” are still being written. In a world where more and more of our stacks include components that are, by design, non-deterministic, we have a rare opportunity: to get curious early, experiment while things are still fluid, and help redefine what good engineering looks like - especially around inference, orchestration and agents - bringing the discipline, judgement and curiosity that make these systems something people can trust.